Version Control

Last updated on 2025-07-01 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is version control and why should I use it?

- How do I get set up to use Git?

- Where does Git store information?

Objectives

- Understand the benefits of an automated version control system.

- Understand the basics of how automated version control systems work.

- Configure

gitthe first time it is used on a computer. - Understand the meaning of the

--globalconfiguration flag. - Create a local Git repository.

- Describe the purpose of the

.gitdirectory.

Motivation

Jimmy and Alfredo have been hired by Ratatouille restaurant (a special restaurant from Euphoric State University) to investigate if it is possible to make the best recipes archive ever. Before even starting, they make a plan of how they want to accomplish this task, and come up with the following requirements:

- The want to be able to work on recipes at the same time, with minimal coordination, and make sure they do not overwrite each other’s changes.

- The want to be able to look back at the history of a recipe, and see who has added what to that recipe.

- They also would like to be able, at any time, to go back to an older version of any recipe.

A colleague suggests using version control to manage

their work. Alfredo and Luigi look at what version control systems are

available, and end up choosing Git, since it is widely used

- it is pretty much the de-facto standard in this area. Throughout this

course we will follow Luigi and Alfredo on their journey learning and

using Git.

Automatic Version Control

What Is Automatic Version Control?

Automatic version control is a system that tracks changes to files over time, allowing multiple people to collaborate, revert to previous versions, and maintain a history of modifications. It is commonly used in software development to manage source code, but it can also be used for documents, configurations, and other digital assets.

Using version control has many benefits, the most important being:

Nothing that is committed to version control is ever lost, unless you work really, really hard at losing it. Since all old versions of files are saved, it’s always possible to go back in time to see exactly who wrote what on a particular day, or what version of a program was used to generate a particular set of results.

As we have this record of who made what changes when, we know who to ask if we have questions later on, and, if needed, revert to a previous version, much like the “undo” feature in an editor.

When several people collaborate in the same project, it’s possible to accidentally overlook or overwrite someone’s changes. The version control system automatically notifies users whenever there’s a conflict between one person’s work and another’s.

Teams are not the only ones to benefit from version control: lone researchers can benefit immensely. Keeping a record of what was changed, when, and why is extremely useful for all researchers if they ever need to come back to the project later on (e.g., a year later, when memory has faded).

Version control is the lab notebook of the digital world: it’s what professionals use to keep track of what they’ve done and to collaborate with other people. Every large software development project relies on it, and most programmers use it for their small jobs as well. And it isn’t just for software: books, papers, small data sets, and anything that changes over time or needs to be shared can and should be stored in a version control system.

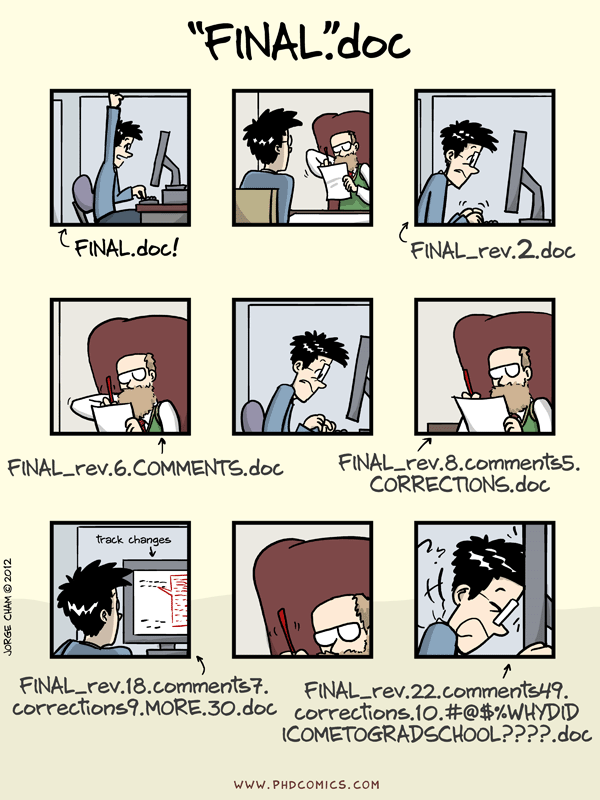

We’ll start by exploring how version control can be used to keep track of what one person did and when. Even if you aren’t collaborating with other people, automated version control is much better than this situation:

We’ve all been in this situation before: it seems unnecessary to have multiple nearly-identical versions of the same document. Some word processors let us deal with this a little better, such as Microsoft Word’s Track Changes, Google Docs’ version history, or LibreOffice’s Recording and Displaying Changes.

Version control systems start with a base version of the document and then record changes you make each step of the way. You can think of it as a recording of your progress: you can rewind to start at the base document and play back each change you made, eventually arriving at your more recent version.

Once you think of changes as separate from the document itself, you can then think about “playing back” different sets of changes on the base document, ultimately resulting in different versions of that document. For example, two users can make independent sets of changes on the same document.

Unless multiple users make changes to the same section of the document - a conflict - you can incorporate two sets of changes into the same base document.

It is the version control system that keeps track of these changes for us, by effectively creating different versions of our files. It allows us to decide which changes will be made to the next version (each record of these changes is called a commit), and keeps useful metadata about them. The complete history of commits for a particular project and their metadata make up a repository. Repositories can be kept in sync across different computers, facilitating collaboration among different people.

The Long History of Version Control Systems

Automated version control systems are nothing new. Tools like RCS, CVS, or Subversion have been around since the early 1980s and are used by many large companies. However, many of these are now considered legacy systems (i.e., outdated) due to various limitations in their capabilities. More modern systems, such as Git and Mercurial, are distributed, meaning that they do not need a centralized server to host the repository. These modern systems also include powerful merging tools that make it possible for multiple authors to work on the same files concurrently.

Paper Writing

Imagine you drafted an excellent paragraph for a paper you are writing, but later ruin it. How would you retrieve the excellent version of your conclusion? Is it even possible?

Imagine you have 5 co-authors. How would you manage the changes and comments they make to your paper? If you use LibreOffice Writer or Microsoft Word, what happens if you accept changes made using the

Track Changesoption? Do you have a history of those changes?

Recovering the excellent version is only possible if you created a copy of the old version of the paper. The danger of losing good versions often leads to the problematic workflow illustrated in the PhD Comics cartoon at the top of this page.

Collaborative writing with traditional word processors is cumbersome. Either every collaborator has to work on a document sequentially (slowing down the process of writing), or you have to send out a version to all collaborators and manually merge their comments into your document. The ‘track changes’ or ‘record changes’ option can highlight changes for you and simplifies merging, but as soon as you accept changes you will lose their history. You will then no longer know who suggested that change, why it was suggested, or when it was merged into the rest of the document. Even online word processors like Google Docs or Microsoft Office Online do not fully resolve these problems.

Key Points

- Version control is like an unlimited ‘undo’.

- Version control also allows many people to work in parallel.

Introducing Git

In this section we will move away from the general discussion on version control systems, and focus on one modern such system - namely Git - which over the past ten years has emerged as the de-facto standard in this area. One of the main goals of this course is to make you very comfortable with using git, which we believe will greatly help you towards the goal of making robust and reproducible research software. If you want to know more about how git has emerged as the dominant version control system, there are a few interesting articles on its history here, here, and here

Setting Up Git

Prerequisites

- In this episode we use Git from the Unix Shell. Some previous experience with the shell is expected, but isn’t mandatory.

- It is also assumed that you have already installed Git on your system. If this is not the case, please do this now, by following the download/installation instructions here

When we use Git on a new computer for the first time, we need to configure a few things. Below are a few examples of configurations we will set as we get started with Git:

- our name and email address,

- what our preferred text editor is,

- and that we want to use these settings globally (i.e. for every project).

On a command line, Git commands are written as

git verb options, where verb is what we

actually want to do and options is additional optional

information which may be needed for the verb. So here is

how Alfredo sets up git on his new laptop:

BASH

$ git config --global user.name "Alfredo Linguini"

$ git config --global user.email "a.linguini@ratatouille.fr"Please use your own name and email address instead of Alfredo’s. This user name and email will be associated with your subsequent Git activity, which means that any changes pushed to Git platforms, such as GitHub, BitBucket, GitLab or any other Git host server after this lesson will include this information.

For this lesson, we will be interacting with TU Delft GitLab instance and so the email address used should be your TUD email.

Line Endings

As with other keys, when you press Enter or ↵ or on Macs, Return on your keyboard, your computer encodes this input as a character. Different operating systems use different character(s) to represent the end of a line. (You may also hear these referred to as newlines or line breaks.) Because Git uses these characters to compare files, it may cause unexpected issues when editing a file on different machines. Though it is beyond the scope of this lesson, you can read more about this issue in the Pro Git book.

You can change the way Git recognizes and encodes line endings using

the core.autocrlf command to git config. The

following settings are recommended:

On macOS and Linux:

And on Windows:

Alfredo also has to set his favorite text editor, following this table:

| Editor | Configuration command |

|---|---|

| Atom | $ git config --global core.editor "atom --wait" |

| nano | $ git config --global core.editor "nano -w" |

| BBEdit (Mac, with command line tools) | $ git config --global core.editor "bbedit -w" |

| Sublime Text (Mac) | $ git config --global core.editor "/Applications/Sublime\ Text.app/Contents/SharedSupport/bin/subl -n -w" |

| Sublime Text (Win, 32-bit install) | $ git config --global core.editor "'c:/program files (x86)/sublime text 3/sublime_text.exe' -w" |

| Sublime Text (Win, 64-bit install) | $ git config --global core.editor "'c:/program files/sublime text 3/sublime_text.exe' -w" |

| Notepad (Win) | $ git config --global core.editor "c:/Windows/System32/notepad.exe" |

| Notepad++ (Win, 32-bit install) | $ git config --global core.editor "'c:/program files (x86)/Notepad++/notepad++.exe' -multiInst -notabbar -nosession -noPlugin" |

| Notepad++ (Win, 64-bit install) | $ git config --global core.editor "'c:/program files/Notepad++/notepad++.exe' -multiInst -notabbar -nosession -noPlugin" |

| Kate (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "kate" |

| Gedit (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "gedit --wait --new-window" |

| Scratch (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "scratch-text-editor" |

| Emacs | $ git config --global core.editor "emacs" |

| Vim | $ git config --global core.editor "vim" |

| VS Code | $ git config --global core.editor "code --wait" |

It is possible to reconfigure the text editor for Git whenever you

want to change it. For now, let’s select vim as our editor,

unless you have a strong preference for something else.

Exiting Vim

Note that Vim is the default editor for many programs. If you haven’t

used Vim before and wish to exit a session without saving your changes,

press Esc then type :q! and press

Enter or ↵ or on Macs, Return. If you

want to save your changes and quit, press Esc then type

:wq and press Enter or ↵ or on Macs,

Return.

Git (2.28+) allows configuration of the name of the branch created

when you initialize any new repository. Alfredo decides to use that

feature to set it to main so it matches the cloud service

he will eventually use.

Default Git branch naming

Source file changes are associated with a “branch.” For new learners

in this lesson, it’s enough to know that branches exist, and this lesson

uses one branch. By default, Git will create a branch called

master when you create a new repository with

git init (as explained in the next section). This term

evokes the racist practice of human slavery and the software development

community has moved to adopt more inclusive language.

In 2020, most Git code hosting services transitioned to using

main as the default branch. As an example, any new

repository that is opened in GitHub and GitLab default to

main. However, Git has not yet made the same change. As a

result, local repositories must be manually configured have the same

main branch name as most cloud services.

For versions of Git prior to 2.28, the change can be made on an

individual repository level. The command for this is in the next

episode. Note that if this value is unset in your local Git

configuration, the init.defaultBranch value defaults to

master.

The five commands we just ran above only need to be run once: the

flag --global tells Git to use the settings for every

project, in your user account, on this computer.

Let’s review those settings with the list command:

If necessary, you change your configuration using the same commands to choose another editor or update your email address. This can be done as many times as you want.

Proxy

In some networks you need to use a proxy. If this is the case, you may also need to tell Git about the proxy:

To disable the proxy, use

Git Help and Manual

Always remember that if you forget the subcommands or options of a

git command, you can access the relevant list of options

typing git <command> -h or access the corresponding

Git manual by typing git <command> --help, e.g.:

While viewing the manual, remember the : is a prompt

waiting for commands and you can press Q to exit the

manual.

More generally, you can get the list of available git

commands and further resources of the Git manual typing:

Key Points

- Use

git configwith the--globaloption to configure a user name, email address, editor, and other preferences once per machine.

Creating a Git Repository

Once Git is configured, we can start using it.

We will help Alfredo with his new project, create a repository with all his recipes.

First, let’s create a new directory in the Desktop

folder for our work and then change the current working directory to the

newly created one:

Then we tell Git to make recipes a repository -- a place where Git can

store versions of our files:

It is important to note that git init will create a

repository that can include subdirectories and their files—there is no

need to create separate repositories nested within the

recipes repository, whether subdirectories are present from

the beginning or added later. Also, note that the creation of the

recipes directory and its initialization as a repository

are completely separate processes.

If we use ls to show the directory’s contents, it

appears that nothing has changed:

But if we add the -a flag to show everything, we can see

that Git has created a hidden directory within recipes

called .git:

OUTPUT

. .. .gitGit uses this special subdirectory to store all the information about

the project, including the tracked files and sub-directories located

within the project’s directory. If we ever delete the .git

subdirectory, we will lose the project’s version control history.

We can now start using one of the most important git commands, which

is particularly helpful to beginners. git status tells us

the status of our project, and better, a list of changes in the project

and options on what to do with those changes. We can use it as often as

we want, whenever we want to understand what is going on.

OUTPUT

On branch main

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)If you are using a different version of git, the exact

wording of the output might be slightly different.

Places to Create Git Repositories

Along with tracking information about recipes (the project we have

already created), Alfredo would also like to track information about

desserts specifically. Alfredo creates a desserts project

inside his recipes project with the following sequence of

commands:

BASH

$ cd ~/Desktop # return to Desktop directory

$ cd recipes # go into recipes directory, which is already a Git repository

$ ls -a # ensure the .git subdirectory is still present in the recipes directory

$ mkdir desserts # make a sub-directory recipes/desserts

$ cd desserts # go into desserts subdirectory

$ git init # make the desserts subdirectory a Git repository

$ ls -a # ensure the .git subdirectory is present indicating we have created a new Git repositoryIs the git init command, run inside the

desserts subdirectory, required for tracking files stored

in the desserts subdirectory?

No. Alfredo does not need to make the desserts

subdirectory a Git repository because the recipes

repository will track all files, sub-directories, and subdirectory files

under the recipes directory. Thus, in order to track all

information about desserts, Alfredo only needed to add the

desserts subdirectory to the recipes

directory.

Additionally, Git repositories can interfere with each other if they

are “nested”: the outer repository will try to version-control the inner

repository. Therefore, it’s best to create each new Git repository in a

separate directory. To be sure that there is no conflicting repository

in the directory, check the output of git status. If it

looks like the following, you are good to go to create a new repository

as shown above:

OUTPUT

fatal: Not a git repository (or any of the parent directories): .gitCorrecting git init Mistakes

Jimmy explains to Alfredo how a nested repository is redundant and

may cause confusion down the road. Alfredo would like to go back to a

single git repository. How can Alfredo undo his last

git init in the desserts subdirectory?

Background

Removing files from a Git repository needs to be done with caution. But we have not learned yet how to tell Git to track a particular file; we will learn this in the next episode. Files that are not tracked by Git can easily be removed like any other “ordinary” files with

Similarly a directory can be removed using

rm -r dirname. If the files or folder being removed in this

fashion are tracked by Git, then their removal becomes another change

that we will need to track, as we will see in the next episode.

Solution

Git keeps all of its files in the .git directory. To

recover from this little mistake, Alfredo can remove the

.git folder in the desserts subdirectory by running the

following command from inside the recipes directory:

But be careful! Running this command in the wrong directory will

remove the entire Git history of a project you might want to keep. In

general, deleting files and directories using rm from the

command line cannot be reversed. Therefore, always check your current

directory using the command pwd.

Key Points

-

git initinitializes a repository. - Git stores all of its repository data in the

.gitdirectory.

Command Line or Graphical Tools?

It is possible to use Git from either the command line

(e.g. GitBash) or through a variety of visual tools, such

as Sourcetree,

TortoiseGit,

SmartGit.

Furthermore, most modern integrated development environments such as

PyCharm and

VSCode

provide integrated visual Git tools.

Knowing how to use Git from the command line has definite benefits:

- Helps novice users become more comfortable with Git’s underlying structure and commands

- Gives more precise control at the low level (through command-line options)

- Equips users with the skills to troubleshoot and solve problems that may not be easily addressed with a GUI

- When searching for online resources on specific Git workflows, most information is available as command line instructions; same applies for help/instructions provided by AI Assistants such as ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude

- GUI tools may change their menus/“look and feel” with new releases, while Git commands/options are much more stable

On the other hands, it is important to understand that visual Git tools can greatly improve the overall developer experience as well as increase productivity:

- Graphical Git tools offer an intuitive interface, making it easier for beginners to grasp basic concepts like branching, or viewing the repository’s history

- Certain advanced Git workflows, such as merging and solving conflicts become much more efficient and less error-prone when performed in a visual environment.

Given all these considerations, one of the goals of this course is to make participants comfortable with using Git from the command line, in order to provide them with a solid foundation upon which they can further expand their Git knowledge. At the same time, we are encouraging participants to explore Git visual tools. For the more advanced Git workflows (e.g. reviewing changes, merging, conflict resolution) we also explain how these workflows can be performed using the Git visual tools provided by the PyCharm development environment.

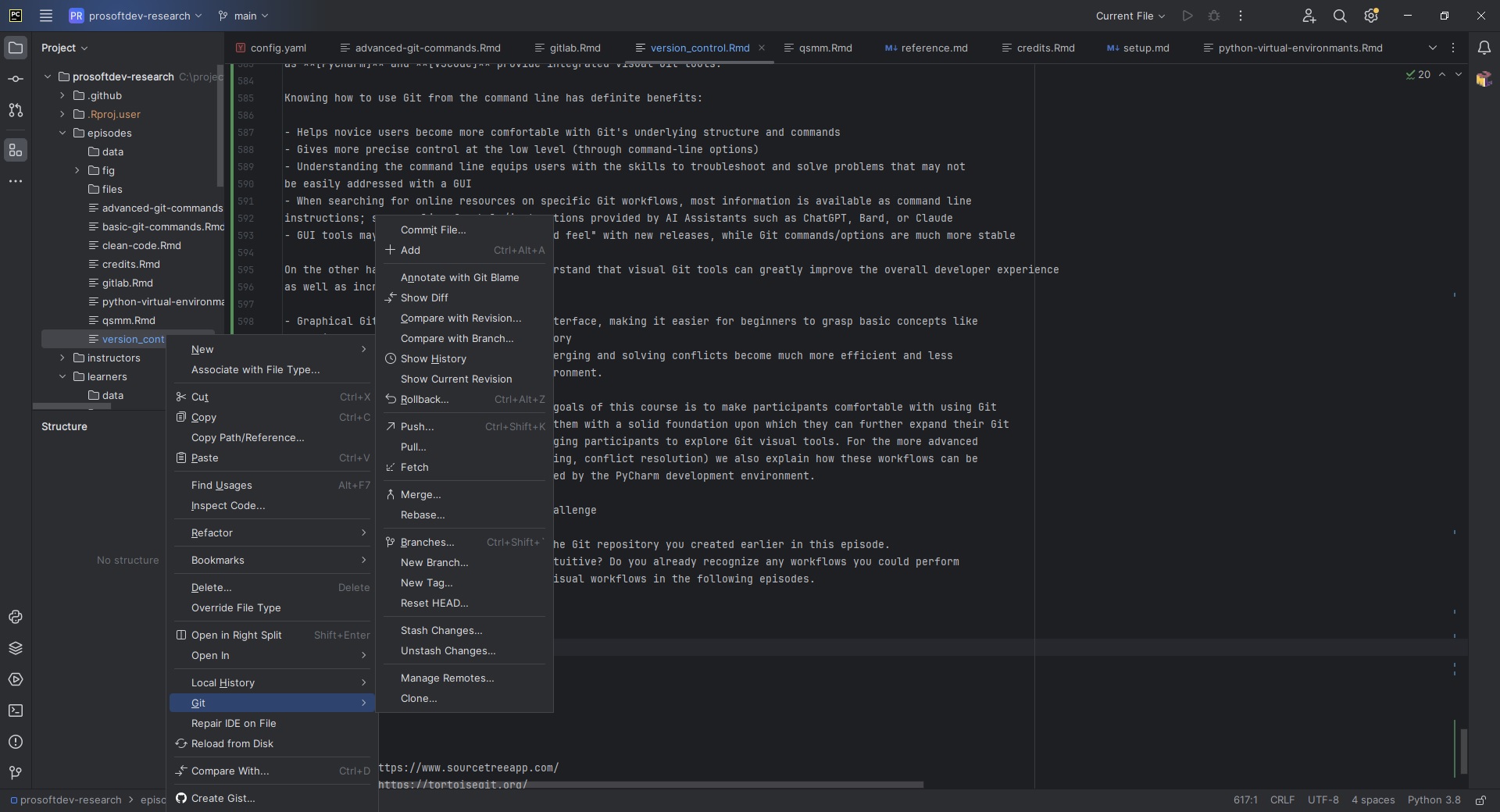

Challenge

Using PyCharm, open the folder containing the Git repository you created earlier in this episode. Locate the Git visual controls. Are they intuitive? Do you already recognize any workflows you could perform from Pycharm? We will cover some of these visual workflows in the following episodes.

Accessing the Git visual tools in PyCharm is done by right-clicking

on a file/folder in the left navigation panel, then selecting

Git from the pop-up menu.

Key Points

- Use git from the command line for maximum control over workflows.

- Using visual tools for some of the advanced Git workflows will increase productivity and reduce errors.