Advanced Git Commands

Last updated on 2025-04-22 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I use version control to collaborate with other people?

- What do I do when my changes conflict with someone else’s?

Objectives

- Clone a remote repository.

- Collaborate by pushing to a common repository.

- Describe the basic collaborative workflow.

- Explain what conflicts are and when they can occur.

- Resolve conflicts resulting from a merge.

Collaborating

For the next step, get into pairs. One person will be the “Owner” and the other will be the “Collaborator”. The goal is that the Collaborator add changes into the Owner’s repository. We will switch roles at the end, so both persons will play Owner and Collaborator.

Practicing By Yourself

If you’re working through this lesson on your own, you can carry on by opening a second terminal window. This window will represent your partner, working on another computer. You won’t need to give anyone access on GitLab, because both ‘partners’ are you.

Adding collaborators to your GitLab repo

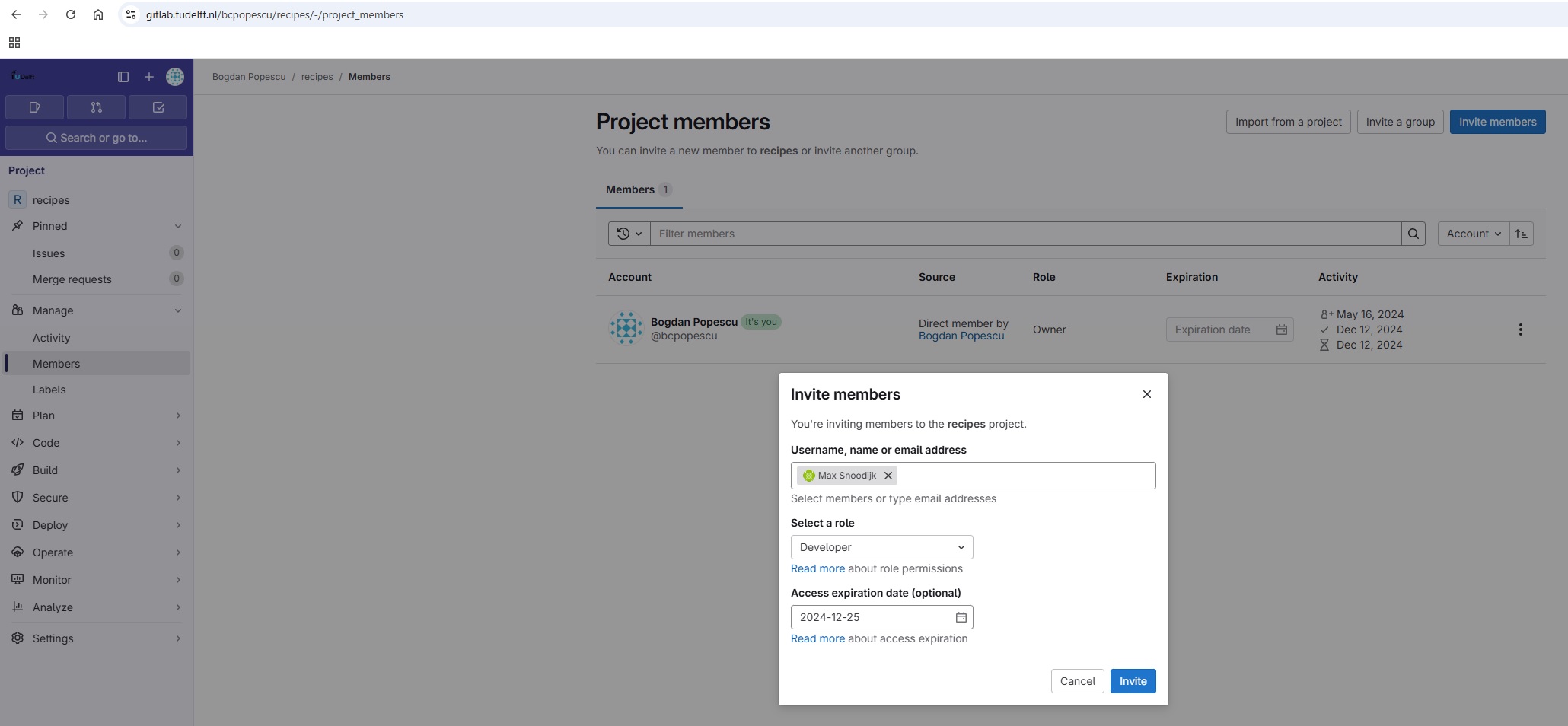

The Owner needs to give the Collaborator access. In your project page on GitLab, click the “Manage” menu on the left panel, then select the “Members” option. On the new “Project members” page (see screenshot below), click on the “Invite members” button, and then fill in the Collaborator’s details as shown below.

Once the Collaborator has been added to the project, they will receive an email instructing them how to accept the invitation and access the project

Cloning a remote GitLab repo

Next, the Collaborator needs to download a copy of the Owner’s repository to her machine. This is called “cloning a repo”.

The Collaborator doesn’t want to overwrite her own version of

recipes.git, so needs to clone the Owner’s repository to a

different location than her own repository with the same name.

To clone the Owner’s repo into her projects folder, the

Collaborator enters:

Replace ‘alflin’ with the Owner’s username.

If you choose to clone without the clone path

(~/projects/alflin-recipes) specified at the end, you will

clone inside your own recipes folder! Make sure to navigate to the

projects folder first.

Making changes

The Collaborator can now make a change in her clone of the Owner’s repository, exactly the same way as we’ve been doing before:

OUTPUT

# Hummus

## Ingredients

* chickpeas

* lemon

* olive oil

* saltOUTPUT

1 file changed, 6 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 hummus.mdThen push the change to the Owner’s repository on GitLab:

OUTPUT

Enumerating objects: 4, done.

Counting objects: 4, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 306 bytes, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To gitlab.tudelft.nl:alflin/recipes.git

9272da5..29aba7c main -> mainNote that we didn’t have to create a remote called

origin: Git uses this name by default when we clone a

repository. (This is why origin was a sensible choice

earlier when we were setting up remotes by hand.)

Take a look at the Owner’s repository on GitLab again, and you should be able to see the new commit made by the Collaborator. You may need to refresh your browser to see the new commit.

Some more about remotes

In this episode and the previous one, our local repository has had a

single “remote”, called origin. A remote is a copy of the

repository that is hosted somewhere else, that we can push to and pull

from, and there’s no reason that you have to work with only one. For

example, on some large projects you might have your own copy in your own

GitLab account (you’d probably call this origin) and also

the main “upstream” project repository (let’s call this

upstream for the sake of examples). You would pull from

upstream from time to time to get the latest updates that

other people have committed.

Remember that the name you give to a remote only exists locally. It’s

an alias that you choose - whether origin, or

upstream, or alfred - and not something

intrinsic to the remote repository.

The git remote family of commands is used to set up and

alter the remotes associated with a repository. Here are some of the

most useful ones:

-

git remote -vlists all the remotes that are configured (we already used this in the last episode) -

git remote add [name] [url]is used to add a new remote -

git remote remove [name]removes a remote. Note that it doesn’t affect the remote repository at all - it just removes the link to it from the local repo. -

git remote set-url [name] [newurl]changes the URL that is associated with the remote. This is useful if it has moved, e.g. to a different GitLab account, or from GitLab to a different hosting service. Or, if we made a typo when adding it! -

git remote rename [oldname] [newname]changes the local alias by which a remote is known - its name. For example, one could use this to changeupstreamtoalfred.

Sync-ing changes made by collaborators

To download the Collaborator’s changes from GitLab, the Owner now enters:

OUTPUT

remote: Enumerating objects: 4, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (4/4), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 3 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From gitlab.tudelft.nl:alflin/recipes

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

9272da5..29aba7c main -> origin/main

Updating 9272da5..29aba7c

Fast-forward

hummus.md | 5 +

1 file changed, 5 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 hummus.mdNow the three repositories (Owner’s local, Collaborator’s local, and Owner’s on GitLab) are back in sync.

A Basic Collaborative Workflow

In practice, it is good to be sure that you have an updated version

of the repository you are collaborating on, so you should

git pull before making our changes. The basic collaborative

workflow would be:

- update your local repo with

git pull origin main, - make your changes and stage them with

git add, - commit your changes with

git commit -m, and - upload the changes to GitLab with

git push origin main

It is better to make many commits with smaller changes rather than of one commit with massive changes: small commits are easier to read and review.

Switch Roles and Repeat

Switch roles and repeat the whole process.

Review Changes

The Owner pushed commits to the repository without giving any information to the Collaborator. How can the Collaborator find out what has changed with command line? And on GitLab?

On the command line, the Collaborator can use

git fetch origin main to get the remote changes into the

local repository, but without merging them. Then by running

git diff main origin/main the Collaborator will see the

changes output in the terminal.

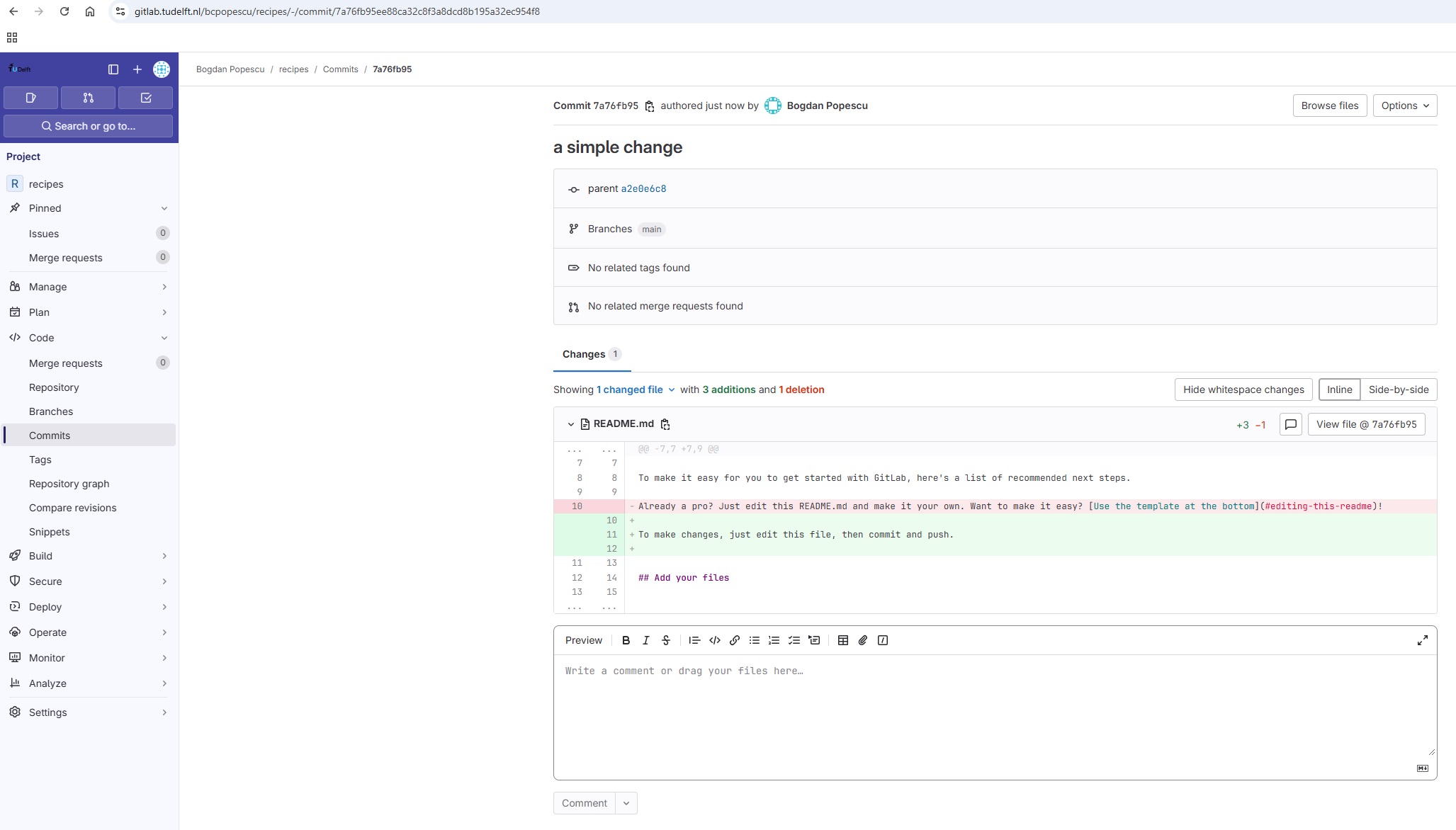

On GitLab, the Collaborator can go to the project and click on the “Code” menu on the left panel, and from there select the “Commits” option. This will open a new page on the right panel, showing the commits history for that project. By clicking on such a commit, the user can see the changes made per file, which will be highlighted by GitLab as shown below.

Version History, Backup, and Version Control

Some backup software can keep a history of the versions of your files. They also allows you to recover specific versions. How is this functionality different from version control? What are some of the benefits of using version control, Git and GitLab?

Solving Conflicts

As soon as people can work in parallel, they’ll likely step on each other’s toes. This will even happen with a single person: if we are working on a piece of software on both our laptop and a server in the lab, we could make different changes to each copy. Version control helps us manage these conflicts by giving us tools to resolve overlapping changes.

To see how we can resolve conflicts, we must first create one. The

file guacamole.md currently looks like this in both

partners’ copies of our recipes repository:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## InstructionsLet’s add a line to the collaborator’s copy only:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## Instructions

* put one avocado into a bowl.and then push the change to GitLab:

OUTPUT

[main 5ae9631] First step on the instructions

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)OUTPUT

Enumerating objects: 5, done.

Counting objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 331 bytes | 331.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), completed with 2 local objects.

To gitlab.tudelft.nl:alflin/recipes.git

29aba7c..dabb4c8 main -> mainNow let’s have the owner make a different change to their copy without updating from GitLab:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## Instructions

* peel the avocadosWe can commit the change locally:

OUTPUT

[main 07ebc69] Add first step

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)but Git won’t let us push it to GitLab:

OUTPUT

To https://gitlab.tudelft.nl/alflin/recipes.git

! [rejected] main -> main (fetch first)

error: failed to push some refs to 'https://gitlab.tudelft.nl:alflin/recipes.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do

hint: not have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing

hint: to the same ref. You may want to first integrate the remote changes

hint: (e.g., 'git pull ...') before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.Telling Git how to solve conflicts

If you see the below in your output, Git is asking what it should do.

OUTPUT

hint: You have divergent branches and need to specify how to reconcile them.

hint: You can do so by running one of the following commands sometime before

hint: your next pull:

hint:

hint: git config pull.rebase false # merge (the default strategy)

hint: git config pull.rebase true # rebase

hint: git config pull.ff only # fast-forward only

hint:

hint: You can replace "git config" with "git config --global" to set a default

hint: preference for all repositories. You can also pass --rebase, --no-rebase,

hint: or --ff-only on the command line to override the configured default per

hint: invocation.In newer versions of Git it gives you the option of specifying different behaviours when a pull would merge divergent branches. In our case we want ‘the default strategy’. To use this strategy run the following command to select it as the default thing git should do.

Then attempt the pull again.

The git pull command updates the local repository to

include those changes already included in the remote repository. After

the changes from remote branch have been fetched, Git detects that

changes made to the local copy overlap with those made to the remote

repository, and therefore refuses to merge the two versions to stop us

from trampling on our previous work. The conflict is marked in in the

affected file:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## Instructions

<<<<<<< HEAD

* peel the avocados

=======

* put one avocado into a bowl.

>>>>>>> dabb4c8c450e8475aee9b14b4383acc99f42af1dOur change is preceded by

<<<<<<< HEAD. Git has then inserted

======= as a separator between the conflicting changes and

marked the end of the content downloaded from GitLab with

>>>>>>>. (The string of letters and

digits after that marker identifies the commit we’ve just

downloaded.)

It is now up to us to edit this file to remove these markers and reconcile the changes. We can do anything we want: keep the change made in the local repository, keep the change made in the remote repository, write something new to replace both, or get rid of the change entirely. Let’s replace both so that the file looks like this:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## Instructions

* peel the avocados and put them into a bowl.To finish merging, we add guacamole.md to the changes

being made by the merge and then commit:

OUTPUT

On branch main

All conflicts fixed but you are still merging.

(use "git commit" to conclude merge)

Changes to be committed:

modified: guacamole.md

OUTPUT

[main 2abf2b1] Merge changes from GitLabNow we can push our changes to GitLab:

OUTPUT

Enumerating objects: 10, done.

Counting objects: 100% (10/10), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done.

Writing objects: 100% (6/6), 645 bytes | 645.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 6 (delta 4), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (4/4), completed with 2 local objects.

To https://gitlab.tudelft.nl:alflin/recipes.git

dabb4c8..2abf2b1 main -> mainGit keeps track of what we’ve merged with what, so we don’t have to fix things by hand again when the collaborator who made the first change pulls again:

OUTPUT

remote: Enumerating objects: 10, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (10/10), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 6 (delta 4), reused 6 (delta 4), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (6/6), done.

From https://gitlab.tudelft.nl:alflin/recipes.git

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

dabb4c8..2abf2b1 main -> origin/main

Updating dabb4c8..2abf2b1

Fast-forward

guacamole.md | 2 +-

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)We get the merged file:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## Instructions

* peel the avocados and put them into a bowl.We don’t need to merge again because Git knows someone has already done that.

How to minimize the chance of conflicts

Git’s ability to resolve conflicts is very useful, but conflict resolution costs time and effort, and can introduce errors if conflicts are not resolved correctly. If you find yourself resolving a lot of conflicts in a project, consider these technical approaches to reducing them:

- Pull from upstream more frequently, especially before starting new work

- Use topic branches to segregate work, merging to main when complete

- Make smaller more atomic commits

- Push your work when it is done and encourage your team to do the same to reduce work in progress and, by extension, the chance of having conflicts

- Where logically appropriate, break large files into smaller ones so that it is less likely that two authors will alter the same file simultaneously

Conflicts can also be minimized with project management strategies:

- Clarify who is responsible for what areas with your collaborators

- Discuss what order tasks should be carried out in with your collaborators so that tasks expected to change the same lines won’t be worked on simultaneously

- If the conflicts are stylistic churn (e.g. tabs vs. spaces),

establish a project convention that is governing and use code style

tools (e.g.

htmltidy,perltidy,rubocop, etc.) to enforce, if necessary

Solving Conflicts that You Create

Clone the repository created by your instructor. Add a new file to it, and modify an existing file (your instructor will tell you which one). When asked by your instructor, pull her changes from the repository to create a conflict, then resolve it.

Conflicts on Non-textual files

What does Git do when there is a conflict in an image or some other non-textual file that is stored in version control?

Let’s try it. Suppose Alfredo takes a picture of its guacamole and

calls it guacamole.jpg.

If you do not have an image file of guacamole available, you can create a dummy binary file like this:

OUTPUT

-rw-r--r-- 1 alflin 57095 1.0K Mar 8 20:24 guacamole.jpgls shows us that this created a 1-kilobyte file. It is

full of random bytes read from the special file,

/dev/urandom.

Now, suppose Alfredo adds guacamole.jpg to his

repository:

OUTPUT

[main 8e4115c] Add picture of guacamole

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 guacamole.jpgSuppose that Jimmy has added a similar picture in the meantime. His

is a picture of a guacamole with nachos, but it is also called

guacamole.jpg. When Alfredo tries to push, he gets a

familiar message:

OUTPUT

To https://gitlab.tudelft.nl/alflin/recipes.git

! [rejected] main -> main (fetch first)

error: failed to push some refs to 'https://gitlab.tudelft.nl:alflin/recipes.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do

hint: not have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing

hint: to the same ref. You may want to first integrate the remote changes

hint: (e.g., 'git pull ...') before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.We’ve learned that we must pull first and resolve any conflicts:

When there is a conflict on an image or other binary file, git prints a message like this:

OUTPUT

$ git pull origin main

remote: Counting objects: 3, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From https://gitlab.tudelft.nl:alflin/recipes.git

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

6a67967..439dc8c main -> origin/main

warning: Cannot merge binary files: guacamole.jpg (HEAD vs. 439dc8c08869c342438f6dc4a2b615b05b93c76e)

Auto-merging guacamole.jpg

CONFLICT (add/add): Merge conflict in guacamole.jpg

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.The conflict message here is mostly the same as it was for

guacamole.md, but there is one key additional line:

OUTPUT

warning: Cannot merge binary files: guacamole.jpg (HEAD vs. 439dc8c08869c342438f6dc4a2b615b05b93c76e)Git cannot automatically insert conflict markers into an image as it does for text files. So, instead of editing the image file, we must check out the version we want to keep. Then we can add and commit this version.

On the key line above, Git has conveniently given us commit

identifiers for the two versions of guacamole.jpg. Our

version is HEAD, and Jimmy’s version is

439dc8c0.... If we want to use our version, we can use

git checkout:

BASH

$ git checkout HEAD guacamole.jpg

$ git add guacamole.jpg

$ git commit -m "Use image of just guacamole instead of with nachos"OUTPUT

[main 21032c3] Use image of just guacamole instead of with nachosIf instead we want to use Jimmy’s version, we can use

git checkout with Jimmy’s commit identifier,

439dc8c0:

BASH

$ git checkout 439dc8c0 guacamole.jpg

$ git add guacamole.jpg

$ git commit -m "Use image of guacamole with nachos instead of just guacamole"OUTPUT

[main da21b34] Use image of guacamole with nachos instead of just guacamoleWe can also keep both images. The catch is that we cannot keep them under the same name. But, we can check out each version in succession and rename it, then add the renamed versions. First, check out each image and rename it:

BASH

$ git checkout HEAD guacamole.jpg

$ git mv guacamole.jpg guacamole-only.jpg

$ git checkout 439dc8c0 guacamole.jpg

$ mv guacamole.jpg guacamole-nachos.jpgThen, remove the old guacamole.jpg and add the two new

files:

BASH

$ git rm guacamole.jpg

$ git add guacamole-only.jpg

$ git add guacamole-nachos.jpg

$ git commit -m "Use two images: just guacamole and with nachos"OUTPUT

[main 94ae08c] Use two images: just guacamole and with nachos

2 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 guacamole-nachos.jpg

rename guacamole.jpg => guacamole-only.jpg (100%)Now both images of guacamole are checked into the repository, and

guacamole.jpg no longer exists.

A Typical Work Session

You sit down at your computer to work on a shared project that is tracked in a remote Git repository. During your work session, you take the following actions, but not in this order:

-

Make changes by appending the number

100to a text filenumbers.txt - Update remote repository to match the local repository

- Celebrate your success with some fancy beverage(s)

- Update local repository to match the remote repository

- Stage changes to be committed

- Commit changes to the local repository

In what order should you perform these actions to minimize the chances of conflicts? Put the commands above in order in the action column of the table below. When you have the order right, see if you can write the corresponding commands in the command column. A few steps are populated to get you started.

| order | action . . . . . . . . . . | command . . . . . . . . . . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| 2 | echo 100 >> numbers.txt |

|

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 | ||

| 6 | Celebrate! |

| order | action . . . . . . | command . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Update local | git pull origin main |

| 2 | Make changes | echo 100 >> numbers.txt |

| 3 | Stage changes | git add numbers.txt |

| 4 | Commit changes | git commit -m "Add 100 to numbers.txt" |

| 5 | Update remote | git push origin main |

| 6 | Celebrate! |

Git Branches

When we do git status, Git also tells us that we are

currently on the main branch of the project. A branch is

one version of your project (the files in your repository) that can

contain its own set of commits. We can create a new branch, make changes

to the code which we then commit to the branch, and, once we are happy

with those changes, merge them back to the main branch. To see what

other branches are available, do:

OUTPUT

* mainAt the moment, there is only one branch (main) and hence

only one version of the code available. When you create a Git repository

for the first time, by default you only get one version (i.e. branch) -

main. Let us have a look at why having different branches

might be useful.

Feature Branch Software Development Workflow

While it is technically OK to commit your changes directly to

main branch, and you may often find yourself doing so for

some minor changes, the best practice is to use a new branch for each

separate and self-contained unit/piece of work you want to add to the

project. This unit of work is also often called a feature and

the branch where you develop it is called a feature branch.

Each feature branch should have its own meaningful name - indicating its

purpose (e.g. “issue23-fix”). If we keep making changes and pushing them

directly to main branch on GitLab, then anyone who

downloads our software from there will get all of our work in progress -

whether or not it is ready to use! So, working on a separate branch for

each feature you are adding is good for several reasons:

- it enables the main branch to remain stable while you and the team explore and test the new code on a feature branch,

- it enables you to keep the untested and not-yet-functional feature branch code under version control and backed up,

- you and other team members may work on several features at the same time independently from one another, and

- if you decide that the feature is not working or is no longer needed - you can easily and safely discard that branch without affecting the rest of the code.

Branches are commonly used as part of a feature-branch workflow, shown in the diagram below.

Git feature branches

Adapted from

Git

Tutorial by sillevl (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License)

In the software development workflow, we typically have a main branch

which is the version of the code that is tested, stable and reliable.

Then, we normally have a development branch (called develop

or dev by convention) that we use for work-in-progress

code. As we work on adding new features to the code, we create new

feature branches that first get merged into develop after a

thorough testing process. After even more testing - develop

branch will get merged into main. The points when feature

branches are merged to develop, and develop to

main depend entirely on the practice/strategy established

in the team. For example, for smaller projects (e.g. if you are working

alone on a project or in a very small team), feature branches sometimes

get directly merged into main upon testing, skipping the

develop branch step. In other projects, the merge into

main happens only at the point of making a new software

release. Whichever is the case for you, a good rule of thumb is -

nothing that is broken should be in

main.

Creating Branches

Let us create a develop branch to work on:

This command does not give any output, but if we run

git branch again, without giving it a new branch name, we

can see the list of branches we have - including the new one we have

just made.

OUTPUT

develop

* mainThe * indicates the currently active branch. So how do

we switch to our new branch? We use the git switch command

with the name of the branch:

OUTPUT

Switched to branch 'develop'

Updating Branches

If we start updating and committing files now, the commits will

happen on the develop branch and will not affect the

version of the code in main. We add and commit things to

develop branch in the same way as we do to

main.

Let us make a small modification to guacamole.md and,

say, change “peel the avocados” to “Peel the avocados”

to see updating branches in action.

If we do:

OUTPUT

On branch develop

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: guacamole.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Git is telling us that we are on branch develop and

which tracked files have been modified in our working directory.

We can now add and commit the changes in

the usual way.

Currently Active Branch

Remember, add and commit commands always

act on the currently active branch. You have to be careful and aware of

which branch you are working with at any given moment.

git status can help with that, and you will find yourself

invoking it very often.

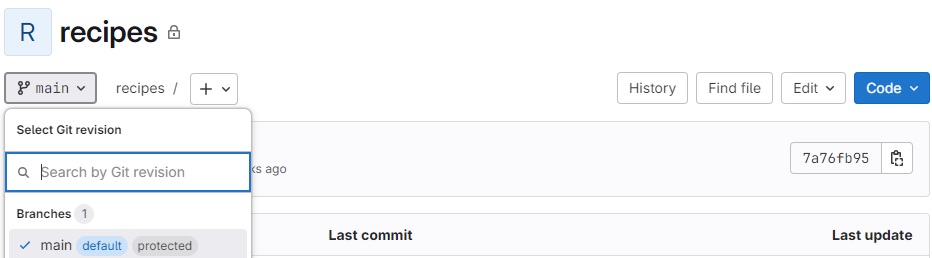

Pushing New Branch Remotely

We push the contents of the develop branch to GitLab in

the same way as we pushed the main branch. However, as we

have just created this branch locally, it still does not exist in our

remote repository. You can check that in GitLab by listing all

branches.

To push a new local branch remotely for the first time, you could use

the -u flag and the name of the branch you are creating and

pushing to:

Git Push With -u Flag

Using the -u switch with the git push

command is a handy shortcut for: (1) creating the new remote branch and

(2) setting your local branch to automatically track the remote one at

the same time. You need to use the -u switch only once to

set up that association between your branch and the remote one

explicitly. After that you could simply use git push

without specifying the remote repository, if you wished so. We still

prefer to explicitly state this information in commands.

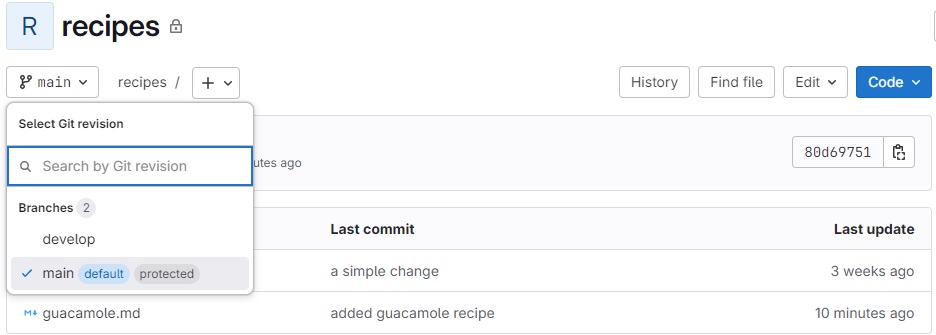

Let us confirm that the new branch develop now exist

remotely on GitLab too. From your repository main page in GitLab, click

the branch dropdown menu (currently showing the default branch

main). You should see your develop branch in

the list too.

You may also have noticed GitLab’s notification about the latest push

to your develop branch just on top of the repository files

and branches drop-down menu.

Now the others can check out the develop branch too and

continue to develop code on it.

After the initial push of the new branch, each next time we push to

it in the usual manner (i.e. without the -u switch):

What is the Relationship Between Originating and New Branches?

It is natural to think that new branches have a parent/child relationship with their originating branch, but in actual Git terms, branches themselves do not have parents but single commits do. Any commit can have zero parents (a root, or initial, commit), one parent (a regular commit), or multiple parents (a merge commit), and using this structure, we can build a ‘view’ of branches from a set of commits and their relationships. A common way to look at it is that Git branches are really only lightweight, movable pointers to commits. So as a new commit is added to a branch, the branch pointer is moved to the new commit.

What this means is that when you accomplish a merge between two branches, Git is able to determine the common ‘commit ancestor’ through the commits in a ‘branch’, and use that common ancestor to determine which commits need to be merged onto the destination branch. It also means that, in theory, you could merge any branch with any other at any time… although it may not make sense to do so!

Merging Into Main Branch

Once you have tested your changes on the develop branch,

you will want to merge them onto the main branch. To do so,

make sure you have committed all your changes on the

develop branch and then switch to main:

OUTPUT

Switched to branch 'main'

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.To merge the develop branch on top of main

do:

OUTPUT

Updating 80d6975..a96062c

Fast-forward

guacamole.md | 2 +-

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)If there are no conflicts, Git will merge the branches without

complaining and replay all commits from develop on top of

the last commit from main. If there are merge conflicts

(e.g. a team collaborator modified the same portion of the same file you

are working on and checked in their changes before you), the particular

files with conflicts will be marked and you will need to resolve those

conflicts and commit the changes before attempting to merge again. Since

we have no conflicts, we can now push the main branch to

the remote repository:

All Branches Are Equal

In Git, all branches are equal - there is nothing special about the

main branch. It is called that by convention and is created

by default, but it can also be called something else. A good example is

gh-pages branch which is often the source branch for

website projects hosted on GitHub (rather than main).

Keeping Main Branch Stable

Good software development practice is to keep the main

branch stable while you and the team develop and test new

functionalities on feature branches (which can be done in parallel and

independently by different team members). The next step is to merge

feature branches onto the develop branch, where more

testing can occur to verify that the new features work well with the

rest of the code (and not just in isolation). We talk more about

different types of code testing in one of the following episodes.

Merge Requests in GitLab

In addition to merging branches through the command line, it is also possible to perform a Merge Request in GitLab. To see how this works, switch back to the develop branch in the recipes repo, and modify the guacamole recipe - by adding one extra line for the ‘Instructions’: ‘Add salt’. Commit your changes, and push them to GitLab.

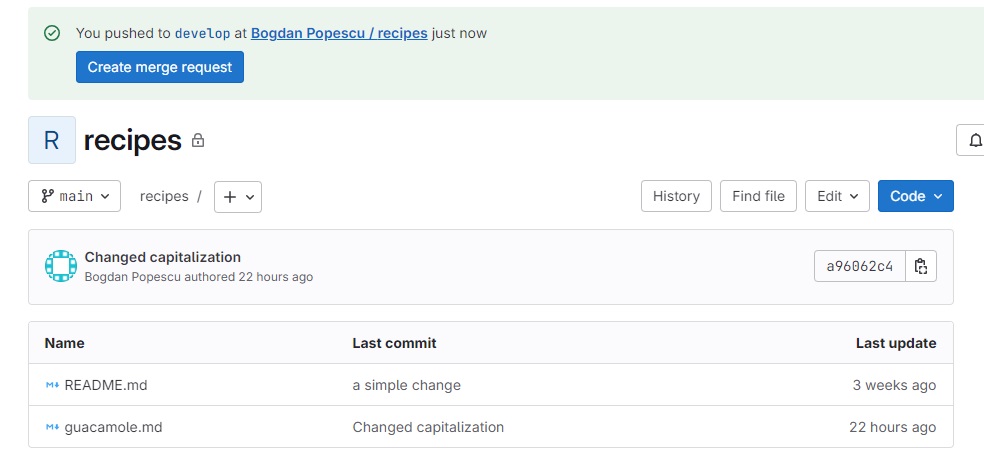

When you reload your GitLab repo main page, you should see that GitLab now gives you the option to create a ‘Merge Request’ to merge your changes in develop to main:

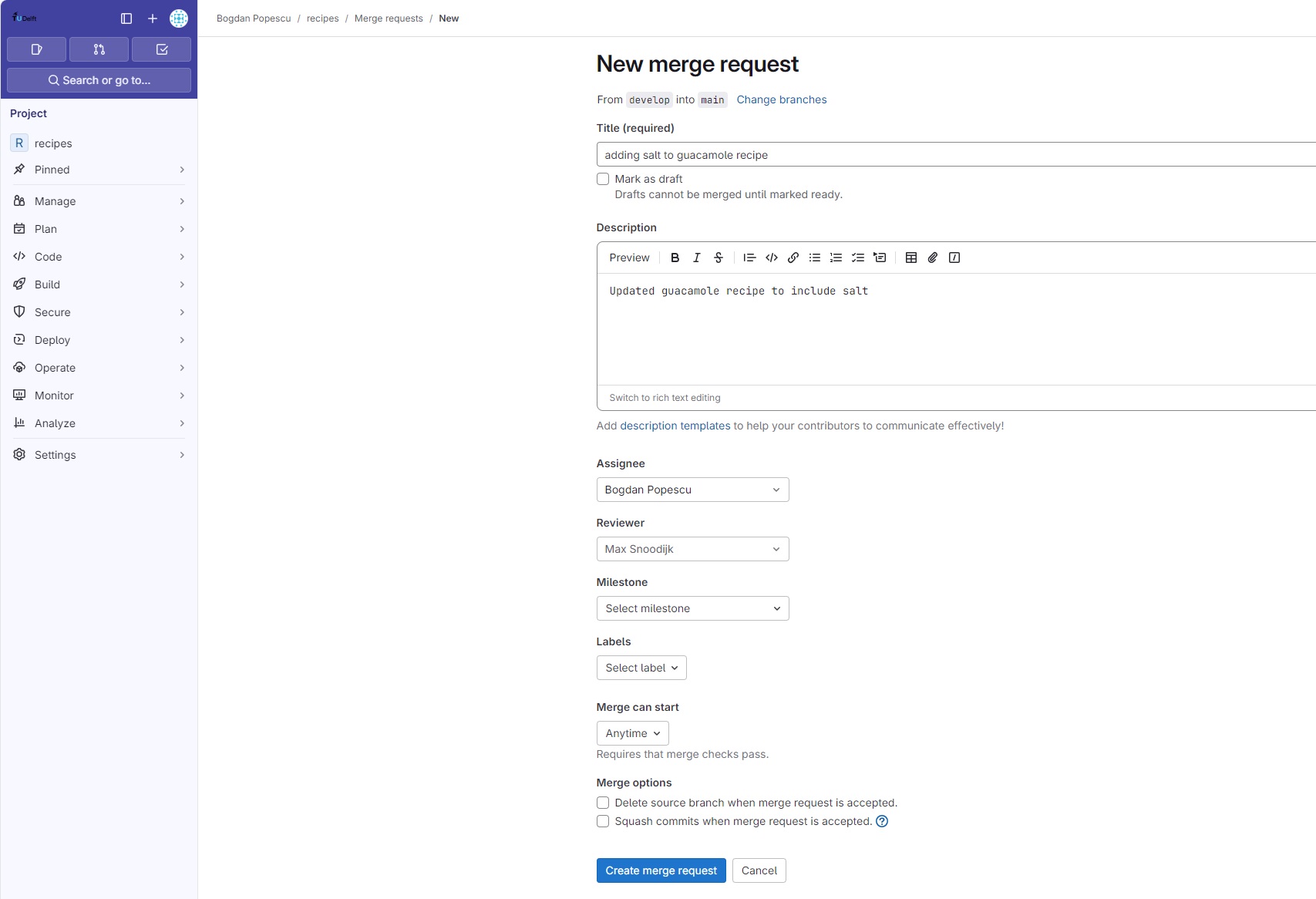

When clicking the “Create merge request” button, GitLab will open a new Merge Request form:

There you can fill details abut this merge, such as the Title and Description, as well as some process-related fields, such as the Asignee and Reviewer. It is good practice to always have a reviewer for any significant code changes. Many large software projects have strict governance rules requiring for example at least one reviewer approval before merging to the main branch, and it is even possible to even configure GitLab to enforce such policies. For now, we advise you to setup informal review rules with your colleagues when working on a joint project.

Once a merge request has been created, GitLab provides process controls for managing its lifecycle:

This form can be accessed from the “Merge requests” menu on the left tab. On this form you can perform actions such as: - approve the merge request by clicking the “Approve” button. - do the actual (Git) merge by clicking the “Merge” button. - review the commits part of this merge request in the “Commits” tab - review the code changes part of this merge request in the “Changes” tab - comment on code changes, also from the “Changes” tab. When making a comment, GitLab notifies the asignee for the merge request about the comment via email.

Key Points

-

git clonecopies a remote repository to create a local repository with a remote calledoriginautomatically set up. - Conflicts occur when two or more people change the same lines of the same file.

- The version control system does not allow people to overwrite each other’s changes blindly, but highlights conflicts so that they can be resolved.

- A branch is one version of your project that can contain its own set of commits.

- Feature branches enable us to develop / explore / test new code

features without affecting the stable

maincode. - GitLab merge requests provide a structured process approach to Git branch merging

Hands-on Project

- Work in groups of two

- Create a GitLab project on the TUD GitLab server

- Assign project roles to each team member

- Create a shared (text) document representing a joint research paper.

- Each member works independently on different sections of the document in separate branches.

- Show how merging can be done without conflicts

- Start working on the same section creating a conflict

- show how it can be solved using GitLab merge requests and Git conflict resolution

Comment Changes in GitLab

The Collaborator has some questions about one line change made by the Owner and has some suggestions to propose.

With GitLab, it is possible to comment on a commit. Over the line of code to comment, a blue comment icon appears to open a comment window. In that window, the Collaborator can post their comments. When a comment is posted, GitLab will inform the author of the commit about it by email, and then the author can address the comment using the same GitLab web interface.